|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

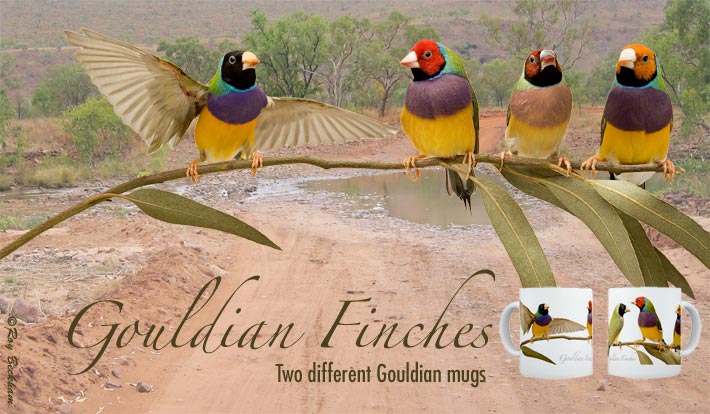

| Gouldian Finch - Chloebia gouldiae (changing to Erythrura gouldiae) | ||||||

|

||||||

| Yellow Headed Gouldian Finch male | ||||||

|

Common Names Description Female: The female has more subdued colors on her chest, belly and back. The female's beak will turn from a pearly white to black when she is in breeding condition. Diet

Gouldians will lay surprising large clutches of eggs. They average 5-8 eggs, but larger clutches are not that unusual. Incubation will normally begin pretty early with some starting after the first egg or two. The pair will share incubation duties during the day, but quite often the male will stay outside during the night. This actually isn't that surprising since Gouldians are not a 'clumping' species. That is to say the pair will sit side-by-side or clump together with each other or others of their species. After 13-14 days of incubation the young begin to hatch. They are small, pink and lack any fuzz. They are easily identified by the light-reflecting nodes at the corners of their mouth (see mouth markings). The pair will take turn brooding the young with the male remaining outside during the night. After about 10 to 14 days, depending upon the size of the clutch, the female will also begin sleeping outside the box at night. This may seem early since the chicks have barely started to get pin feathers, but they seem to be just fine even if the nighttime temperatures move down to the low 30's. I think it is important to have lights on for an active period of about 14 to 15 hours. If raised outdoors, the long winter nights may be too long for the chicks to go without food. Especially if it is cold. The chicks will fledge at approximately 22-25 days. At this point they will be a dusky green with a buff belly (see juveniles). Once the chicks fledge, many will not return to the nest at night, but will stay out with the parents. This is variable. It seems that if the parents return to roost in the nest, then the chicks will return with them. The parents will continue to feed the chicks for an additional 2-3 weeks. During this time, the female will usually begin to lay another clutch of eggs. It has always been my practice to remove any clutches of eggs that are laid before the previous clutch has been weaned. This is to give the parents a little break to build up some body reserves before they begin feeding another clutch of young and quite often incubation is sporadic, the young soil the eggs and the hatch rate is far lower than usual. This clutch of removed eggs can easily be fostered to Society finches for them to raise. After the young are weaned and removed from the parents, the pair will usually lay another full clutch of eggs and incubate and raise that that clutch normally. The young, sometimes referred to as 'greens', can take up to 9 months to fully molt into adult plumage. Usually though, they are complete within 4-6 months depending upon temperature. Some breeders report higher than usual losses from their Gouldians as they molt into adult colors and that this is due to their 'higher' protein requirement. I have not found this to be the case and suffer no greater losses from young Gouldians than my Zebra finches. They do have a higher protein requirement than a Zebra, but this is not that unusual. It is the Zebra and Society finch that has an unusually low protein requirement. Given the proper diet which includes proteins and fats as well as the carbohydrates from their seeds, young Gouldians are hardy birds. I have always bred my Gouldians in cages as individual pairs. I have tried breeding them in larger cages with 2 to 3 pairs, but was not as successful with that arrangement. Some other breeders have reported great success breeding Gouldians in colonies. Probably the best arrangement for colony breeding would be in a larger aviary with four or more pairs. While a mostly peaceful bird, they can begin to pick on each other to defend their nest territory. Some Gouldian pairs can be notorious chick tossers. Often incubating well, but then ejecting the young soon after hatching. It is usually the male that ejects the young, but not always. I feel that these are mostly young pairs or birds that are not yet in full breeding condition. I have found that it is a waste of time to return the chicks (if they are found alive) to the nest as they will most certainly be ejected again. The young can be fostered to another pair of Gouldians or Society finches. If possible, try to pair up an older bird with a younger bird and wait until the birds are in top breeding condition before providing a nest box. I check the beak color of the pair as an indicator of breeding condition. Males should have pearly white beaks with a red tip and females should have an almost completely black beak (note: mutations can mask these beak colors).

The mutations developed in aviculture include the White Breast (replaces the normal purple color with white), the Yellow-backed (eliminates the blue & black color), and the Blue-backed (eliminates the yellow color). How these mutation act on the birds and the combinations can be confusing for many Gouldian breeders. Head color - The Red-headed variety (RH) is sex-linked dominant morph that can be held as single or double factor in the males, while females only need inherit one gene from their father to show the red mask. Males that are single factor RH can produce both BH and RH hens. Yellow head (or orange as it is really a rust orange color) is a recessive morph, but it requires the presence of the RH gene to be visible. If the bird is a YH (has two genes for YH), but is genetically Black headed, then the head mask will be black. The tip of the beak will be yellow rather than red, however. Red head and Black headed birds that are split for YH show no visible signs of the hidden gene. Breast color - The White Breast mutation is a recessive mutation. It eliminates the purple color leaving a clean white breast. This is inherited separately from head color and can be combined with any of the three morphs. The Lilac breast mutation seems to be tied to the White breast mutation in some way. It is unclear as to it's mode of inheritance and may simply be the incomplete suppression of the purple color by the White breasted gene. Males with a lilac breast are sometimes confused with hens. The deep yellow coloration of the belly will help differentiate these males from normal females. Back color - The Blue-backed variety is a recessive mutation. It eliminates the yellow color on the Gouldian and alters the colors accordingly. The normally green back is changed to blue, the yellow belly is changed to a dingy white and if the bird is either Red or Yellow headed, then this is changed to a salmon color. The beak is pearly white without any tip color so there is no way to distinguish between RH and YH Blue-backed birds. The mask looks the same. Only if the genetics are known can you say for certain. I paired two normal YH Goulds split for Blue-back to produce true YH Blue-backed birds. These looked identical to other Blue-backs exhibiting salmon colored heads. Some of which were surely RHs genetically. Yellow-back is a Sex-linked Co-dominant mutation in the US and Europe. (There is a autosomal recessive mutation in Australia and South Africa.) The mutation works to suppress the blue and black color from the bird. The normally green back is changed to yellow, the black face ring is removed and genetically BH birds will have a gray face mask. Males that hold the Yellow back gene in the single factor (only one gene inherited) will have a diluted appearance. They still have green on their backs, but this is diluted and the black face ring is eliminated or reduced. There is a twist here, if a single factor Yellow-backed male is also a White Breasted bird, he will be visually a Yellow-backed. There is often some flecks of green on the back, but he certainly is not a dilute. Females cannot be split for sex-linked mutations so they only need inherit one Yellow-back gene to be visually Yellow. Therefore, dilute females can never be produced regardless of the breast color. The combination of the two back colors results in a pale bird that only faintly shows the colors that were removed. These are called Silvers. Personally, I see little point to their development as it is the elimination of all the color that makes the Gouldian such a magnificent bird. |

| Naturally Occurring Color Morphs | |

| Red Headed - males (above, middle of page) | Normal wild state |

| Black Headed male (click to view) | Sex-linked Recessive |

| Yellow (Orange) Headed male (Top of page) | Autosomal Recessive. Also require Red Head to be present |

| Mutations Developed in Aviculture (USA) | |

| Blue Backed RH male (click to view) | Autosomal Recessive |

| Blue Backed BH female (click to view) | |

| Yellow Backed White Breasted YH male (click to view) | |

| Yellow Backed White Breasted RH male (click to view) | Co-dominant Sex-linked. Males in single factor are dilutes |

| White Breasted RH male (click to view) | Autosomal Recessive |

| Lilac Breasted | Autosomal Recessive. Possible link to White Breast |

| Dilute Males | A single factor Yellow Backed male. No females can be produced |

| Silvers | A combination of Yellow back and Blue Back |

| Lutino | Sex-linked recessive (USA) Autosomal recessive in Europe/Japan |

|

Additional Notes Gouldian finches are becoming somewhat rare in the wild and are considered endangered. Some of this is due to changes in the environment, and there was some evidence that pointed to the spread of Air Sac mites as the cause of their decline. However, recent studies have focused on the burning of grass that is routinely conducted in Australia. Aboriginal people would burn the grasses to burn off dried grass and encourage new growth. Cattlemen of today use a different method of burning at a later part of the year that results in really hot fires that destroy seeds and spinefex before it can form seed heads. These changes combined with the lack of suitable nesting sites may be at the root of the Gouldian's decline in the wild. The light reflecting nodes in the corners of their mouth as well as the mouth markings themselves points to a close relationship with parrot finches (see mouth markings). |